From Dec 2009

| e |

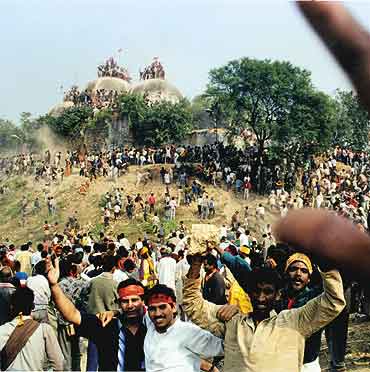

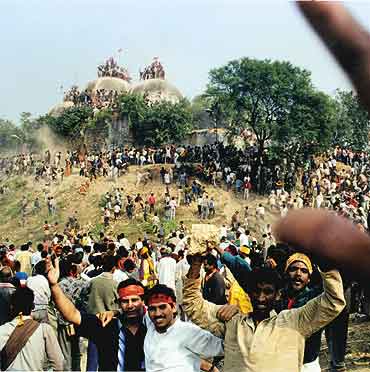

Recently, there was a bit of a furore in India when the report of theLiberhan Commission was published. This was a commission, headed by a Justice M S Liberhan, which was charged – in December 1992 – with inquiring into the demolition of an old mosque called the Babri Masjid by Hindunazi goons on 6 December 1992. The commission took all of 17 years to submit its report, which reported that Hindunazi goons – inspired and controlled by the (Hindunazi) Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), later to rule the country for close to a decade, to test nuclear bombs and begin the process that has now made India a US satellite – had demolished the mosque.

This was an amazing revelation in view of the fact that TV cameras had been present and had recorded the demolition in all its sordid detail, including cheering and hugging Hindunazi leaders and the police who either did nothing or encouraged and helped the goons.

17 years? The same conclusions could have been, and had been, reached in 17 days.

Why was this demolition significant? In fact, why had it occurred at all?

The late 1980s was a time of Hindunazi revival in India. The cry was of “Hinduism being in danger”; and the danger was from three fronts.

On one side was the “enemy within”; the favourite epithet applied to them by the Hindunazis was “pseudo-secularists”. These were the people, whether practising Hindus or atheists or agnostics, who thought Muslims, Christians and other potential fifth-columnists deserved the same rights and privileges as anyone else who was a citizen of the country. Anyone who even acknowledged the minorities as human was a potential pseudo-secularist.

The other two enemies were the Christians and the Muslims. The Christians existed in small, mostly tribal pockets, and could be left to be pinched off at leisure at a later date. The Muslims were a more credible enemy; after all, they comprised almost 15% of the population and although they were in reality a poor and disadvantaged minority, who were (and are) systematically discriminated against in education, employment and even provision of services like water and electricity, they could be projected as frightening enemies who would outbreed and swamp the Hindus and make them “second class citizens in their own country”.

Unfortunately, most Hindus were too busy making a living to buy this rhetoric. Something else was needed, and this old, semi-derelict mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, was perfect; one might call it a godsend.

One of the two great epics of India is the Ramayana; the mythical god-king hero of that epic, Ram, was allegedly born in Ayodhya. Furthermore, there was, allegedly, a temple at the precise site of his birth, and this alleged temple was allegedly demolished by the first Mughal Emperor, Babur, to construct a mosque. That mosque was the Babri Masjid.

So the Hindunazis built a campaign around a pledge to remove the mosque and rebuild the grand – and utterly unproven – temple that the Mughals had supposedly demolished. It was called the Ram Janmabhoomi (Birthplace) agitation. (I don’t know if I was the only one who called it the Rum Janmabhoomi agitation and suggested the mosque should be converted into a brewery. It’s such an obvious pun that I’d be astonished if nobody else had thought of it.)

The matter was in court, in fact had been in court since the late 1940s, and – given the dazzling speed of the Indian legal system – will probably be in court a hundred years from now. But the Hindunazis declared they didn’t care what the courts said. For them it was a matter of faith. They believed (or chose to pretend to believe) that Ram actually had existed, had been born in Ayodhya, and that a temple on the precise and exact spot of his birth had been demolished to make way for the Babri Masjid. What the courts said, and what the facts were, didn’t count.

So – as the late eighties gave way to the nineties – the Hindunazis built up their campaign with the Ram Temple as the symbol of the perfect Hindu nation they would create out of secular India, where non-Hindus could, in the words of Hindunazi hero V D Savarkar, exist only if they demanded and expected nothing, not even human rights.

It was in that situation, with tempers running high, that I arrived in Lucknow – not far from Ayodhya –as a callow eighteen-year-old, to study dentistry.

There were Hindunazi supporters even among my fellow-students. I remember in 1990 some of them went on a “pilgrimage” to Ayodhya, missing classes to do so, and brought back packets of Ram stickers which they applied to the clothes of the rest of us, regardless of religion or lack thereof. Only those of us from other parts of the country, like me, pulled the stickers off and threw them away. The rest decided discretion was the better part of valour. Many of the Hindunazi group were politically connected to the college administration of the time.

So things went along till December 1992, with pro-Ram Temple rallies, threats to take matters into Hindu hands, etc, etc. Then, on 6 December 1992, a carefully orchestrated “spontaneous” movement of massed Hindunazi stormtroopers in saffron headbands with demolition training stormed the mosque past inactive state police cordons (the Hindunazi state government refused to allow central armed police forces, which were nearby though not at the actual spot, to act) and destroyed it in a matter of hours.

The national government at the centre was under the Congress party, which while not Hindunazi flirted openly with Hindu right-wing policies, something known as “soft Hindutva”. It had – ignoring intelligence reports – more or less allowed the situation to develop that allowed the demolition to take place. It could have coerced the state government into upholding the law or dismissed it and imposed direct central rule, but did neither.

As the country exploded in Hindu-Muslim rioting, with the Muslims not always at the receiving end, let me interrupt this narrative to bring you some personal memories of those days. My memories of 6 December are fairly clear; those of the subsequent days have merged and blurred, and it’s no longer possible for me to say what happened on precisely which day and in what sequence.

6 Dec, afternoon: I’m visited by my friend Felix Mboya (who as I mentioned in a blog last year is a cousin of Barack Obama). He and I sit in the open-air cafe outside my hostel (inside the college campus) with thick sweet biscuits and tea, talking. Suddenly I’m told by someone that something’s happened to the Babri Masjid and curfew will be imposed any moment. Felix isn’t from the college; he studies in the University and lives far away, so he leaves at once, without waiting to finish his tea and biscuits. I’m not too worried; I’m going home at the end of the month for winter vacations and I don’t anticipate anything much happening. On an impulse, I buy a packet of buns and take it back to my room. That impulse purchase turned out to be of immense benefit in the following days.

6 Dec evening: The news is everywhere; the Babri Masjid has been demolished. Curfew has been clamped in most parts of the country, but in spite of that rioting has broken out in many cities and towns. The college, which is situated in one of the oldest parts of the city, Chowk (much of which is a warren of very narrow lanes between tall windowless buildings of raw red brick sans paint or plaster), is completely isolated from news. There’s no food. I eat a couple of buns for dinner.

Sometime in the early hours of the morning of 7 December, or it might be 8 December, I’m lining up at a public call office in the college campus to try and call home (this was long before the age of mobile phones, remember). There are so many people waiting that they’re handing out numbers and limiting calls to three minutes. If you can’t get through after three tries (the lines all across the nation are busy) you have to let the next guy have the phone and try again after three more people. The only time I could have got through at all was the early morning, which was why I’m there in the PCO at 3am in the December cold. (I get through and tell them I'm OK; it's the only time I am able to call home in those days.)

One of these mornings (7 or 8 Dec; the days blur in my memory now) I watch an ambulance drive into the college. It was sent to pick up some critically ill person and returned without being able to get through. The windshield is shattered, with only a few triangular shards of glass round the margins. The driver looks shaken and scared, as well he might.

“What happened?” we ask him.

“Boys threw stones,” he says. Stoning ambulances was all the rage if you couldn’t stone police vehicles.

Oddly enough, the college authorities soon put out another story. According to this one, the ambulance wasn’t stoned. The driver hit a buffalo and damaged the vehicle. To this day I’m unable to understand who they thought would buy this story, especially since the ambulance had suffered no damage other than the windscreen. There wasn’t even a dent in the bodywork. A flying mini-buffalo, maybe?

Those first few days, the college administration was also so determined that we should think it was business as usual that they didn’t suspend clinics. They couldn’t run classes because the teachers couldn’t get through from their homes, but we all had to go to the clinic and sit there without work or patients, stewing in boredom until we could return to our hostels again. (A possibly interesting titbit: the dental college building was separated from the main college campus by a street that was always crammed with traffic. It was only when, during that curfew, I saw that street for the first time free of pedestrians and traffic that I noticed it wasn’t flat as I’d always assumed; there was actually a marked slope from one end to the other, but this was impossible to see when there were cars, bullock carts, rickshaws, auto-rickshaws, tempos, bicycles, the odd cow, pushcarts and endless masses of humans moving on it.)

We didn’t have food; I survived on my buns for two days, until the kitchens reopened and served us lentils and rice and nothing more. We didn’t have classes and we couldn’t leave the college to go anywhere because of the curfew; and still the college administration was determined to pretend that everything was normal. This reached farcical levels at times.

One evening my friend Simon and I are walking from one hostel to another, where the shop has opened temporarily. We pass in sight of the college’s main entrance. Suddenly, from the streets and the crowded residential areas – virtually brick slums – outside rises a chorus of shrieks and screams, and we can see a reddish glow. The shop can wait; we literally run back to our hostel.

The college authorities officially deny anything happened. The situation was all improved, they say, and the classes will soon resume. This despite the fact that we still don’t have real food, and that the curfew is still on most of the time, and that extremely strong rumours are going around that the scheduled winter vacations at the end of the month will be brought forward and these enforced idle days will be declared the winter vacations.

At this time the students of the junior, preclinical classes decide they’ve had enough. They make plans to go home if they can catch one of the few and very irregular trains running. Normally, there used to be about five trains a day running between Delhi and North East India, for instance; during these riots there are not more than one every two days, if that. We of the third and fourth year classes finally decide to join them. There’s a train passing through Lucknow on the 12th of December (I remember the date); we’ll be on it along with the juniors.

On the 11th evening, there’s a notice up on every notice board from the college administration, signed by the principal, at the time a paediatrician named PK Mishra whose administrative skills aren’t known to be particularly great. The notice declares that there is no, repeat no, substance to the rumours that the vacations will be brought forward. Classes would resume very shortly and those students who disregarded the notice and left for home would have to suffer the (unspecified) consequences.

Nevertheless, the junior students decide to go. We of the senior years have more to lose so we decide to stay back. The one train that is scheduled to run will arrive on the evening of the 12th, so the juniors take advantage of the curfew being lifted during the afternoon and leave for the railway station, which is many kilometres away.

It must have been while they were still waiting for the train that the new notice went up. I’m one of the first to read it, at about six or seven in the evening. It’s signed by the selfsame PK Mishra and declares that the winter vacation’s been brought forward, and these days will be treated as the vacation. I told you her administrative skills left something to be desired.

We, the remainder, decide to leave the next morning. There is a branch of the Allahabad Bank in the college, and just about all college students have accounts there, but the bank is still shut. I borrow money from the man in charge of the open air cafe where Felix and I first heard of the demolition. It’s just enough to get me home.

First problem: there’s no train running through Lucknow that day, and nobody can be sure if there’s going to be one tomorrow, either. The only thing to do is get to Kanpur, about a hundred kilometres to the south, and try to pick up a train from there. So we leave the college by a hired tempo (for those not in the know, it’s a vehicle rather like a tuk-tuk, noisy, uncomfortable, unsafe and polluting, but cheap as a mode of mass transit). Chowk is still under curfew, and the direct route to the railway station is closed. The tempo takes the long way round, via Hazratganj, where curfew’s been lifted long ago and the shops and traffic are perfectly normal. I’m surprised, because Hazratganj hadn’t seen any lesser rioting than Chowk had, and that wasn’t much. But Hazratganj – unlike Chowk – isn’t an area dominated by Muslims, and the government has different rules for different communities. Riding in that tempo, I remember thinking that if I were a Muslim I’d have had questions about why Chowk is still under curfew.

We drive to Kanpur in a juddering old bus crammed with people. All night, we sit in the dingy and crowded waiting room in Kanpur’s railway station, and once in a while walk around the platform and watch gigantic rats run around the railway tracks. I buy and read a copy of “Parade” magazine. I still remember an article about “warmonger” Saddam Hussein’s alleged “Supergun”. Well, it was a magazine devoted to the outpourings of the less highbrow American press, so no wonder.

Late the next morning the train arrives, already about twelve hours late. It’s crammed with people and I remember almost suffocating that night on the train – for long periods of time I could literally not expand my chest to breathe. Somehow, we survive to reach our destinations. That’s a victory.

Postscript: Now that the Liberhan Commission’s submitted its ancient report, what happens? Answer: Nothing. The report doesn’t recommend action against anyone. It’s not dropped any bombshells and is high on rhetoric and low on particulars. The principal Hindunazi leader it indicts, Lal Krishna Advani, is already a spent force in politics and is an embarrassment to his party, the BJP.

The Congress can’t do a thing to him without making him a martyr to the Hindunazi cause. Its own sins of omission and commission are so many that they can’t be kept hidden if any action is to be taken. So what is going to happen is what normally happens in India: a lot of hot air.

In the meantime, the Babri Masjid has been erased, not just in formal existence but in popular terminology. It’s now always called, by the media and the politicians, the “disputed structure”. Where it stood is a makeshift temple, hidden behind multiple security barriers, to which a thin trickle of pilgrims comes. The grand Ram temple of Hindunazi dreams was never built, and seems likely never to be built. Some half-completed pillars and stones lie around a site in Ayodhya called Karsevakpuram (after the “kar sevaks”, the Hindunazi stormtroopers who demolished the mosque), but no work has been done on them in years. Some of the priests of the many, many other temples in Ayodhya, and some Hindunazi leaders, still talk of the need to build a temple, but nobody really pays them any attention.

Ram no longer pays political dividends. People are simply not interested anymore.

This was an amazing revelation in view of the fact that TV cameras had been present and had recorded the demolition in all its sordid detail, including cheering and hugging Hindunazi leaders and the police who either did nothing or encouraged and helped the goons.

17 years? The same conclusions could have been, and had been, reached in 17 days.

Why was this demolition significant? In fact, why had it occurred at all?

The late 1980s was a time of Hindunazi revival in India. The cry was of “Hinduism being in danger”; and the danger was from three fronts.

On one side was the “enemy within”; the favourite epithet applied to them by the Hindunazis was “pseudo-secularists”. These were the people, whether practising Hindus or atheists or agnostics, who thought Muslims, Christians and other potential fifth-columnists deserved the same rights and privileges as anyone else who was a citizen of the country. Anyone who even acknowledged the minorities as human was a potential pseudo-secularist.

The other two enemies were the Christians and the Muslims. The Christians existed in small, mostly tribal pockets, and could be left to be pinched off at leisure at a later date. The Muslims were a more credible enemy; after all, they comprised almost 15% of the population and although they were in reality a poor and disadvantaged minority, who were (and are) systematically discriminated against in education, employment and even provision of services like water and electricity, they could be projected as frightening enemies who would outbreed and swamp the Hindus and make them “second class citizens in their own country”.

Unfortunately, most Hindus were too busy making a living to buy this rhetoric. Something else was needed, and this old, semi-derelict mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, was perfect; one might call it a godsend.

One of the two great epics of India is the Ramayana; the mythical god-king hero of that epic, Ram, was allegedly born in Ayodhya. Furthermore, there was, allegedly, a temple at the precise site of his birth, and this alleged temple was allegedly demolished by the first Mughal Emperor, Babur, to construct a mosque. That mosque was the Babri Masjid.

So the Hindunazis built a campaign around a pledge to remove the mosque and rebuild the grand – and utterly unproven – temple that the Mughals had supposedly demolished. It was called the Ram Janmabhoomi (Birthplace) agitation. (I don’t know if I was the only one who called it the Rum Janmabhoomi agitation and suggested the mosque should be converted into a brewery. It’s such an obvious pun that I’d be astonished if nobody else had thought of it.)

The matter was in court, in fact had been in court since the late 1940s, and – given the dazzling speed of the Indian legal system – will probably be in court a hundred years from now. But the Hindunazis declared they didn’t care what the courts said. For them it was a matter of faith. They believed (or chose to pretend to believe) that Ram actually had existed, had been born in Ayodhya, and that a temple on the precise and exact spot of his birth had been demolished to make way for the Babri Masjid. What the courts said, and what the facts were, didn’t count.

So – as the late eighties gave way to the nineties – the Hindunazis built up their campaign with the Ram Temple as the symbol of the perfect Hindu nation they would create out of secular India, where non-Hindus could, in the words of Hindunazi hero V D Savarkar, exist only if they demanded and expected nothing, not even human rights.

It was in that situation, with tempers running high, that I arrived in Lucknow – not far from Ayodhya –as a callow eighteen-year-old, to study dentistry.

There were Hindunazi supporters even among my fellow-students. I remember in 1990 some of them went on a “pilgrimage” to Ayodhya, missing classes to do so, and brought back packets of Ram stickers which they applied to the clothes of the rest of us, regardless of religion or lack thereof. Only those of us from other parts of the country, like me, pulled the stickers off and threw them away. The rest decided discretion was the better part of valour. Many of the Hindunazi group were politically connected to the college administration of the time.

So things went along till December 1992, with pro-Ram Temple rallies, threats to take matters into Hindu hands, etc, etc. Then, on 6 December 1992, a carefully orchestrated “spontaneous” movement of massed Hindunazi stormtroopers in saffron headbands with demolition training stormed the mosque past inactive state police cordons (the Hindunazi state government refused to allow central armed police forces, which were nearby though not at the actual spot, to act) and destroyed it in a matter of hours.

The national government at the centre was under the Congress party, which while not Hindunazi flirted openly with Hindu right-wing policies, something known as “soft Hindutva”. It had – ignoring intelligence reports – more or less allowed the situation to develop that allowed the demolition to take place. It could have coerced the state government into upholding the law or dismissed it and imposed direct central rule, but did neither.

As the country exploded in Hindu-Muslim rioting, with the Muslims not always at the receiving end, let me interrupt this narrative to bring you some personal memories of those days. My memories of 6 December are fairly clear; those of the subsequent days have merged and blurred, and it’s no longer possible for me to say what happened on precisely which day and in what sequence.

6 Dec, afternoon: I’m visited by my friend Felix Mboya (who as I mentioned in a blog last year is a cousin of Barack Obama). He and I sit in the open-air cafe outside my hostel (inside the college campus) with thick sweet biscuits and tea, talking. Suddenly I’m told by someone that something’s happened to the Babri Masjid and curfew will be imposed any moment. Felix isn’t from the college; he studies in the University and lives far away, so he leaves at once, without waiting to finish his tea and biscuits. I’m not too worried; I’m going home at the end of the month for winter vacations and I don’t anticipate anything much happening. On an impulse, I buy a packet of buns and take it back to my room. That impulse purchase turned out to be of immense benefit in the following days.

6 Dec evening: The news is everywhere; the Babri Masjid has been demolished. Curfew has been clamped in most parts of the country, but in spite of that rioting has broken out in many cities and towns. The college, which is situated in one of the oldest parts of the city, Chowk (much of which is a warren of very narrow lanes between tall windowless buildings of raw red brick sans paint or plaster), is completely isolated from news. There’s no food. I eat a couple of buns for dinner.

Sometime in the early hours of the morning of 7 December, or it might be 8 December, I’m lining up at a public call office in the college campus to try and call home (this was long before the age of mobile phones, remember). There are so many people waiting that they’re handing out numbers and limiting calls to three minutes. If you can’t get through after three tries (the lines all across the nation are busy) you have to let the next guy have the phone and try again after three more people. The only time I could have got through at all was the early morning, which was why I’m there in the PCO at 3am in the December cold. (I get through and tell them I'm OK; it's the only time I am able to call home in those days.)

One of these mornings (7 or 8 Dec; the days blur in my memory now) I watch an ambulance drive into the college. It was sent to pick up some critically ill person and returned without being able to get through. The windshield is shattered, with only a few triangular shards of glass round the margins. The driver looks shaken and scared, as well he might.

“What happened?” we ask him.

“Boys threw stones,” he says. Stoning ambulances was all the rage if you couldn’t stone police vehicles.

Oddly enough, the college authorities soon put out another story. According to this one, the ambulance wasn’t stoned. The driver hit a buffalo and damaged the vehicle. To this day I’m unable to understand who they thought would buy this story, especially since the ambulance had suffered no damage other than the windscreen. There wasn’t even a dent in the bodywork. A flying mini-buffalo, maybe?

Those first few days, the college administration was also so determined that we should think it was business as usual that they didn’t suspend clinics. They couldn’t run classes because the teachers couldn’t get through from their homes, but we all had to go to the clinic and sit there without work or patients, stewing in boredom until we could return to our hostels again. (A possibly interesting titbit: the dental college building was separated from the main college campus by a street that was always crammed with traffic. It was only when, during that curfew, I saw that street for the first time free of pedestrians and traffic that I noticed it wasn’t flat as I’d always assumed; there was actually a marked slope from one end to the other, but this was impossible to see when there were cars, bullock carts, rickshaws, auto-rickshaws, tempos, bicycles, the odd cow, pushcarts and endless masses of humans moving on it.)

We didn’t have food; I survived on my buns for two days, until the kitchens reopened and served us lentils and rice and nothing more. We didn’t have classes and we couldn’t leave the college to go anywhere because of the curfew; and still the college administration was determined to pretend that everything was normal. This reached farcical levels at times.

One evening my friend Simon and I are walking from one hostel to another, where the shop has opened temporarily. We pass in sight of the college’s main entrance. Suddenly, from the streets and the crowded residential areas – virtually brick slums – outside rises a chorus of shrieks and screams, and we can see a reddish glow. The shop can wait; we literally run back to our hostel.

The college authorities officially deny anything happened. The situation was all improved, they say, and the classes will soon resume. This despite the fact that we still don’t have real food, and that the curfew is still on most of the time, and that extremely strong rumours are going around that the scheduled winter vacations at the end of the month will be brought forward and these enforced idle days will be declared the winter vacations.

At this time the students of the junior, preclinical classes decide they’ve had enough. They make plans to go home if they can catch one of the few and very irregular trains running. Normally, there used to be about five trains a day running between Delhi and North East India, for instance; during these riots there are not more than one every two days, if that. We of the third and fourth year classes finally decide to join them. There’s a train passing through Lucknow on the 12th of December (I remember the date); we’ll be on it along with the juniors.

On the 11th evening, there’s a notice up on every notice board from the college administration, signed by the principal, at the time a paediatrician named PK Mishra whose administrative skills aren’t known to be particularly great. The notice declares that there is no, repeat no, substance to the rumours that the vacations will be brought forward. Classes would resume very shortly and those students who disregarded the notice and left for home would have to suffer the (unspecified) consequences.

Nevertheless, the junior students decide to go. We of the senior years have more to lose so we decide to stay back. The one train that is scheduled to run will arrive on the evening of the 12th, so the juniors take advantage of the curfew being lifted during the afternoon and leave for the railway station, which is many kilometres away.

It must have been while they were still waiting for the train that the new notice went up. I’m one of the first to read it, at about six or seven in the evening. It’s signed by the selfsame PK Mishra and declares that the winter vacation’s been brought forward, and these days will be treated as the vacation. I told you her administrative skills left something to be desired.

We, the remainder, decide to leave the next morning. There is a branch of the Allahabad Bank in the college, and just about all college students have accounts there, but the bank is still shut. I borrow money from the man in charge of the open air cafe where Felix and I first heard of the demolition. It’s just enough to get me home.

First problem: there’s no train running through Lucknow that day, and nobody can be sure if there’s going to be one tomorrow, either. The only thing to do is get to Kanpur, about a hundred kilometres to the south, and try to pick up a train from there. So we leave the college by a hired tempo (for those not in the know, it’s a vehicle rather like a tuk-tuk, noisy, uncomfortable, unsafe and polluting, but cheap as a mode of mass transit). Chowk is still under curfew, and the direct route to the railway station is closed. The tempo takes the long way round, via Hazratganj, where curfew’s been lifted long ago and the shops and traffic are perfectly normal. I’m surprised, because Hazratganj hadn’t seen any lesser rioting than Chowk had, and that wasn’t much. But Hazratganj – unlike Chowk – isn’t an area dominated by Muslims, and the government has different rules for different communities. Riding in that tempo, I remember thinking that if I were a Muslim I’d have had questions about why Chowk is still under curfew.

We drive to Kanpur in a juddering old bus crammed with people. All night, we sit in the dingy and crowded waiting room in Kanpur’s railway station, and once in a while walk around the platform and watch gigantic rats run around the railway tracks. I buy and read a copy of “Parade” magazine. I still remember an article about “warmonger” Saddam Hussein’s alleged “Supergun”. Well, it was a magazine devoted to the outpourings of the less highbrow American press, so no wonder.

Late the next morning the train arrives, already about twelve hours late. It’s crammed with people and I remember almost suffocating that night on the train – for long periods of time I could literally not expand my chest to breathe. Somehow, we survive to reach our destinations. That’s a victory.

Postscript: Now that the Liberhan Commission’s submitted its ancient report, what happens? Answer: Nothing. The report doesn’t recommend action against anyone. It’s not dropped any bombshells and is high on rhetoric and low on particulars. The principal Hindunazi leader it indicts, Lal Krishna Advani, is already a spent force in politics and is an embarrassment to his party, the BJP.

The Congress can’t do a thing to him without making him a martyr to the Hindunazi cause. Its own sins of omission and commission are so many that they can’t be kept hidden if any action is to be taken. So what is going to happen is what normally happens in India: a lot of hot air.

In the meantime, the Babri Masjid has been erased, not just in formal existence but in popular terminology. It’s now always called, by the media and the politicians, the “disputed structure”. Where it stood is a makeshift temple, hidden behind multiple security barriers, to which a thin trickle of pilgrims comes. The grand Ram temple of Hindunazi dreams was never built, and seems likely never to be built. Some half-completed pillars and stones lie around a site in Ayodhya called Karsevakpuram (after the “kar sevaks”, the Hindunazi stormtroopers who demolished the mosque), but no work has been done on them in years. Some of the priests of the many, many other temples in Ayodhya, and some Hindunazi leaders, still talk of the need to build a temple, but nobody really pays them any attention.

Ram no longer pays political dividends. People are simply not interested anymore.

No comments:

Post a Comment